THE ESSENTIAL BRADBURY

As Ray Bradbury’s biographer—having worked with the man for twelve years on four award-winning books and a graphic novel—people often ask, “Where should I begin when reading Ray Bradbury?”

This is always a complicated question. I take my Bradbury seriously.

Often times, particularly with young readers, I like to tailor a reading list that is specific to them and their interests. Bradbury has something to appeal to everyone, so individual instruction is vital when possible. And for young, often reluctant readers, there really is no better bridge author from YA over to heavier, more daunting literature. Bradbury is a gateway drug. He has the power to ignite young readers for life. All it takes is one short story. I passionately believe this, and, as a teacher and writer who has spoken at schools around the world, I know this to be true. And there is so much Bradbury out there to read. The man left us with such a towering legacy. He desperately wanted to live forever. And he has. As the old maxim states: “All passes, art alone endures.”

So, the long answer on where to start? In 2010, Everyman's Library republished The Stories of Ray Bradbury, containing a staggering 100 of Bradbury's best short stories. Along with this, there is the equally voluminous Bradbury Stories, published in 2003, containing yet another 100 more short fictional gems. (Bradbury dedicated this last book, in part to me, a truly stirring gift.) Certainly, you cannot go wrong by reading either of these spectacular volumes. Bradbury is an absolute magician with the short story. It is, in my estimation, his strongest creative form (he wrote novels, poetry, essays, screenplays, teleplays, stage plays; hell, he even created architectural designs). His wife of fifty-six years, Marguerite, agreed with me. Ray Bradbury owned the short story form. But in today’s tech-addled, attention-achallenged world, reading 200 stories between two door-stop volumes is, for many, an unrealistic goal.

So the short answer of where to begin with Bradbury? This list, right here.

So here it is. I offer up a streamlined directory of twenty-five of my personal favorite short fictions by the master of miracles. These stories embody all the trademarks of vintage Bradbury: the lyrical language; the fantastic, original, unforgettable ideas; the rich metaphor; and endings that can startle, surprise, exhilarate, or conjure tears of joy, heartbreak, or both.

This list is entirely subjective. These are my favorites—often for purely sentimental reasons. Here you will get the premise, the history, and the backstory on these mini-masterpieces. I will occasionally share never-before-published items from my own files. And I would love to hear from you. Which twenty-five stories would you select? Tell me.

These stories reflect a wide range, from weird tales, to social science fiction, to quiet and contemplative tales of contemporary literature. These are pure and classic Bradbury—our finest contemporary mythologist, who would have been 100 in 2020. He always told me that he wanted to live to 100. And he has. Through his stories.

Live Forever, Ray Bradbury.

#25 “THE FIRST NIGHT OF LENT”

Where to Find It: A Medicine for Melancholy, The Stories of Ray Bradbury

First Published: Playboy, March, 1956

Plot Synopsis: A young screenwriter at work in Ireland in 1953 discovers that his ever-reliable regular taxicab driver has become dangerous and impaired when behind the wheel. Nick, the village driver, escorts the young writer from Dublin to the Irish countryside and the estate of the young screenwriter’s director. Nick then waits at the local pub until the writer is ready to be driven back to the city. There is never a problem, until the first night of Lent. . . .

Critique: Any “essential” list of Bradbury short stories must include an Irish tale (as well as a Mexico story, a Mars story, and a Green Town story, for that matter). The problem is, of course, which Irish story? I choose this one for two simple reasons. First, Bradbury takes the lyrical quality of his voice and drenches it in a poetic and authentic Irish brogue.

Nick, now. See his easy hands loving the wheel in a slow clocklike turning as soft and silent as winter constellations snow down the sky. Listen to his mist-breathing voice all night-quiet as he charms the road, his foot a tenderly benevolent pat on the whispering accelerator, never a mile under thirty, never two miles over. Nick, Nick and his steady boat gentling a mild sweet lake where all time slumbers. Look, compare. And bind such a man to you with summer grasses, gift him with silver, shake his hand warmly at each journey’s end

“Good night, Nick,” I said at the hotel. “See you tomorrow.”

“God willing,” whispered Nick

And he drove softly away.

The second reason I have selected this story for “The Essential Bradbury” list is that this is the first Irish story Bradbury wrote. It is his first creation, fresh-removed and newly-minted from his own actual experiences of living in Dublin in the autumn of 1953 and the winter of 1954, writing the screenplay for Moby Dick for film director John Huston. From a biographical standpoint, it is fascinating to read a work of short fiction that is, ostensibly, memoir. And with “The First Night of Lent,” Bradbury had discovered a trove of material that would continue to yield rich story, culminating in the publication of the 1992 semi-autobiographical novel, Green Shadows, White Whale, a minor-classic.

The Beginning of the Irish Stories: As Ray recalled, one night after he had returned from Ireland, he was in bed and a voice spoke to him

“Ray, darling!”

Ray responded, “Who is it?”

And the voice said, “It’s Nick, the cab driver who drove you back and forth from Dublin to Kilcock 80 or 90 times. Do you remember that, Ray? Do you?”

And Ray said, “Yes?”

And the voice said, “Would you mind puttin’ it down?”

So Ray Bradbury started writing his Irish stories, beginning with “The First Night of Lent.”

Historical Aside: A fascinating New York Times article on John Huston’s Georgian Irish Manor, ran June 12, 2012. Check it out here.

This is the very house where, in 1953, Nick the cab driver picked Bradbury up late at night, to drive him back to Dublin. This is the very house where Ray sat with John Huston, late into the Irish night, as Huston went over Ray’s adaptation of Moby Dick.

#24 “THE SOUND OF SUMMER RUNNING”

Where to Find It: Dandelion Wine, The Stories of Ray Bradbury

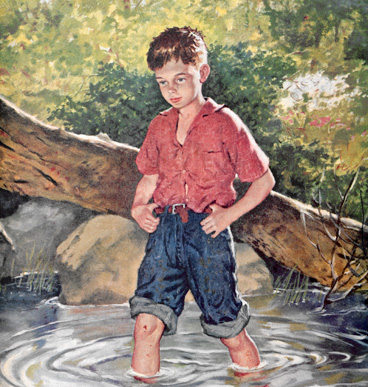

The illustration by Amos Sewell that accompanied the original publication of “Summer in the Air,” in the February 1956 issue of Saturday Evening Post.

First Published as: “Summer in the Air,” The Saturday Evening Post, February 18, 1956

Plot Synopsis: At the beginning of summer, 1928, Douglas Spaulding sees a pair of brand new tennis shoes in a storefront window. His shoes are worn out, his feet feel heavy, and he is convinced that this resplendent pair of Cream-Sponge Para Litefoot Shoes will change his summer forever.

Backstory: Ray Bradbury on the origins of the story from Listen to the Echoes: The Ray Bradbury Interviews:

“I was on a bus going into Westwood a few years ago, and a young boy jumped on the bus, threw his money in the box, raced down the aisle, and threw himself into a seat across from me. And I looked at him, and I said, ‘My god, if I had his energy, I could write a poem every day, a story every week, a novel every month. What’s his secret?’ I looked down at his feet. He had the brightest pair of new fresh tennis shoes on his feet. And I said, ‘oh, my god, I can remember when I was a kid, my father taking me downtown and buying me my first pair of new summer tennis shoes.’ I went home, and I wrote the short story.”

Critique: This story is a shining example of Bradbury’s range as a literary writer. The man did not need an otherworldly landscape or elements of the fantastic to meditate on the human experience. Bradbury found magic in the every day, in this case, in a new pair of tennis shoes and the perspective of youth. The best Bradbury, in my opinion, is rooted in unforgettable story with a philosophical question at its center, all told in his singular, poetic style.

The Prose: Somehow the people who made tennis shoes knew what boys needed and wanted. They put marshmallows and coiled springs in the soles and they wove the rest out of grasses bleached and fired in the wilderness. Somewhere deep in the soft loam of the shoes the thin hard sinews of the buck deer were hidden. The people that made the shoes must have watched a lot of winds blow the trees and a lot of rivers going down to the lakes. Whatever it was, it was in the shoes, and it was summer.

#23 “THE LONG RAIN”

Where to Find It: The Illustrated Man, The Stories of Ray Bradbury

First Published: As “Death-by-Rain” in Planet Stories, September, 1950.

Plot Synopsis: Ray Bradbury writes a Jack London story set on Venus. A marooned crew on the perpetually rain-saturated planet march through the thick and endless planetary jungle world desperately seeking a sun-dome, a man-made structure built by colonists that provides warmth, provisions and respite from the infinite rain.

Cinematic History: Director Jack Smight brought the story to the screen in the 1969 adaptation of the Illustrated Man, a critical and box-office disaster.

Personal Anecdote: No question, this is classic Bradbury. But I am also partial to it. “The Long Rain” is the first Ray Bradbury story I ever read. I was 11-years-old and I was never quite the same again.

Passage of Exemplary Bradburian Prose: "It was a hard rain, a perpetual rain, a sweating and steaming rain; it was a mizzle, a downpour, a fountain, a whipping in the eyes, an undertow at the ankles; it was a rain to drown all rains and the memory of rains."

The Venus Chronicles: Bradbury only penned two Venus stories over the course of his illustrious career and they were both classics. “All Summer in Day” is one of his most anthologized and beloved tales, read around the world in middle school grades. “The Long Rain” is Bradbury in a rare adventure yarn, a thrilling man versus nature narrative.

#22 “IN A SEASON OF CALM WEATHER”

Where to Find It: A Medicine for Melancholy, The Stories of Ray Bradbury

First Published: January 1957, Playboy

Plot Synopsis: A man who idolizes Pablo Picasso encounters his hero creating a masterpiece in the sand on a beach in the South of France.

Backstory: Bradbury got the inspiration for the story one day while walking on the beach along with his wife and some friends. He picked up a discarded Popsicle stick and started etching in the sand. At this point, he thought about a man who always wanted to own a Picasso original and one day stumbled upon the renowned artist creating a masterpiece on the beach. The creation, of course, would last only as long as the tide would stay out.

Critique: An excellent example of Bradbury at his most tightly crafted game. Short and taut, “In a Season of Calm Weather” is just a few pages, but tells a compelling story of celebrating the moment—in this case, the moment on the beach where George Smith watches from afar as his hero creates his masterpiece in the sand. The story also features a seldom discussed example of Bradbury’s appreciation of French prose poetry (See Echoes pgs. 210-211). Bradbury’s lengthy description of Picasso’s sand creation represents his further literary exploration of the highly evocative work of French writer Saint-James Perse.

For there on the flat shore were pictures of Grecian lions and Mediterranean goats and maidens with flesh of sand like powdered gold and satyrs piping on hand-carved horns and children dancing, strewing flowers along and along the beach with lambs gamboling after, and musicians skipping to their harps and lyres and unicorns racing youths toward distant meadows, woodlands, ruined temples, and volcanoes. Along the shore in a never-broken line, the hand, the wooden stylus of this man, bent down in fever and raining perspiration, scribbled, ribboned, looped around over and up, across, in, out, stitched, whispered, stayed, then hurried on as if this traveling bacchanal must flourish to its end before the sun was put out by the sea. Twenty, thirty yards or more the nymphs and dryads and summer founts sprang up in unraveled hieroglyphs. And the sand in the dying light was the color of molten copper on which was now slashed a message that any man in any time might read and savor down the years. Everything whirled and poised in its own wind and gravity. Now wine was being crushed from under the grape-blooded feet of dancing vintners' daughters, now steaming seas gave birth to coin-sheated monsters while flower-red kites strewed scent on blowing clouds...now...now...now...

The artist stopped.

Anecdote: “In a Season of Calm Weather” was produced into the 1969 feature film Picasso Summer starring Albert Finney. The film suffered from myriad production difficulties and has seldom been seen since its original theatrical release. It occasionally airs on late night cable television. Bradbury wrote the screenplay, but it was largely scrapped by the film’s director, Serge Bourguignon. The short story was later collected under the title “Picasso Summer.” Bradbury told me that he actually prefers this title, stating that it is more succinct. From my own point of view, I favor the original story title, as it has the ring of John Steinbeck’s early influence on Bradbury. I also adhere to Bradbury’s own mantra (a mantra he has frequently defied, by the way), that “a writer should never mess with his younger-self” by later rewriting published works.

One Last Point: I firmly maintain that the epic production failure of the 1969 film Picasso Summer—replete with Spanish Bullfighters, arrangements with Pablo Picasso to play himself, and comedian Bill Cosby serving as co-producer—would make for a great short comedic memoir. Ray Bradbury agreed, but due to his advancing age and declining health, this book concept (similar to his autobiographical novel Green Shadows, White Whale) never saw the light.

#21 JUNE 2001: AND THE MOON BE STILL AS BRIGHT

Where to Find It: The Martian Chronicles, Bradbury Stories

First Published: June, 1948, Thrilling Wonder Stories

Plot Synopsis: A cornerstone story in Ray Bradbury’s groundbreaking novel-in-stories, The Martian Chronicles, “And the Moon Be Still as Bright,” follows the arrival of the fourth expedition of Earth men to Mars. The crew quickly discovers that nearly all of the Martians have died from chickenpox, a fatal disease to the natives of Mars, apparently brought by Earth colonists on one of the earlier expeditions. The first successful mission to Mars, the crew of the fourth expedition celebrates their accomplishment by getting drunk, making noise and throwing bottles into the Martian canals. One of the rocket crew, archeologist Jeff Spender, is disgusted by the antics of his fellow crew-mates and their lack of respect for the planet and he goes off the rails to dangerous effect.

Critique: When Ray Bradbury connected his disparate Mars stories in the 1950 story cycle, The Martian Chronicles, one of his intentions was to use the colonization of outer space as an allegory for the westward expansion of the United States in the 1800s. If The Martian Chronicles is to be deemed a work of social commentary—for which it most certainly is—then “And the Moon Be Still as Bright” is the quintessential tale in the book that reflects the nucleus of Bradbury’s social philosophies at the time of its publication. The story clearly addresses the decimation of a native people, as well as humankind’s insidious encroachment upon nature and the accompanying corpratization to follow. 50 years before anyone dared dream of naming sport stadiums after companies, Bradbury forewarned us of the “Rockefeller Canal” and the “DuPont Sea” on Mars. When archeologist Jeff Spender goes berserk and AWOL, disappearing from his rocket crew out into the remote Martian mountains, it is Bradbury at his very best—penning a cautionary tale of social commentary through gripping narrative suspense. Jeff Spender is one of Bradbury’s most multi-faceted characters, a rage-fueled, conflicted hero, a homicidal protagonist who shares Bradbury’s own social and political concerns circa 1950.

Excerpt: “We Earth Men have a talent for ruining big, beautiful things. The only reason we didn’t set up hot-dog stands in the midst of the Egyptian temple of Karnak is because it was out of the way and served no large commercial purpose. And Egypt is a small part of Earth. But here, this whole thing is ancient and different, and we have to set down somewhere and start fouling it up.”

Nerd Detail: The crew member named “Hathaway” was named after a married couple of the same name that lived next door to Ray and his family at 1619 South St. Andrews Place. Ray was 14. In another detail of nomenclature nerdom, a crewmember in the earlier version of the story published in Thrilling Wonder Stories was named “McClure,” Ray’s wife’s maiden name.

#20 “THE SMALL ASSASSIN”

Where to Find It: The October Country, The Stories of Ray Bradbury

First Published: Dime Mystery, November 1946

Plot Synopsis: David and Alice Leiber welcome their first-born child into the world, but Alice quickly becomes convinced something sinister is at play. She senses that her newborn son is resentful for bringing him out from the safety of the womb into the cold, stark world. Alice becomes increasingly paranoid, convinced her evil child wants to kill her.

Critique: When I teach this story to my college classes, students invariably either absolutely love it, or can’t suspend their disbelief at the outlandish concept of a homicidal infant. But this is supernatural horror, so, really, what do the naysayers expect? Readers accept Cthulhu but not a diaper-clad killer?

In my estimation, “The Small Assassin” is early-gothic Bradbury at his creepy best. The story hits many of the themes of classical gothic literature—isolation, dread, descent into madness, and grotesquery—while managing to be a completely fresh and new spin on the genre’s tropes. Written in 1945 when he was just 25 years old, Bradbury was extrapolating the then undiagnosed mental health issue of post-partum depression and looking at it through the lens of horror. Decades before the evil neonatal cinematic classic, Rosemary’s Baby, Ray Bradbury had created the murderous infant tale. “The Small Assassin” also shows Bradbury’s increasing mastery at crafting dark, slowly mounting suspense.

The Autobiographical Connection: Wait…a story about a baby wanting to kill his mother has autobiographical roots? As with most Bradbury stories, the answer is, most decidedly, yes! Let me endeavor to explain: One of the more fantastical tales Bradbury told about his own life over the years was claiming to recall his own birth.

“I was a ten-month baby” Bradbury told me in an interview. “When you stay in the womb for ten months, you develop your eyesight and your hearing. So, when I was born, I remember it.”

In the late 1940s, Bradbury startled his own mother one day by phoning her to tell her of his birth memory. The details her son recalled were uncanny in their accuracy, the color of the room and the placement of the windows, the number of attending physicians and nurses, and much more

Whether Bradbury truly recalled his own birth, or his singular imagination had created a false memory, is unclear. Science, of course, tells us that an infant’s mind is not developed enough to recall birth. But Ray’s response to a scientist who once pointed this argument out was: “I was there, were you?

Either way, Bradbury’s recollection of his birth gave him the idea for “The Small Assassin.” His birth memory instilled in him the philosophy that a baby lives in a comfortable, aphotic universe for nine months (more or less) and, at the end of this period, is rudely, forced out into an all-new, unknown and cold reality. Bradbury purposed that the child in the “Small Assassin” was resentful of his mother for giving birth to him.

So, there you have the autobiographical origins of “The Small Assassin.”

When I travel and speak about Bradbury, fans often ask if I believe that he really remembered his own birth. When I first met Ray in May of 2000, he told me his birth story, and, like many, I was skeptical. I believed that he had imagined his birth, convinced himself that the memory was real, subconsciously constructing his own myth. But after spending thousands of hours with Ray, growing to know him, as he said, “better that he knew himself,” I am now convinced that Ray Bradbury did, indeed, “remember being born.” His memory of the tiniest details of childhood were certainly like none I have ever encountered. His memory was photographic and encyclopedic. He was also a genius.

Unknown Nerd Detail: The parents in “The Small Assassin,” are named Leiber. The doctor who delivered Ray Douglas Bradbury into the world on August 22, 1920 at 4:50 in the afternoon (Yes, he missed “4:51” by one minute!) was also named Leiber. When I pointed this out to Ray, he said this was totally unintentional, an example of his subconscious naming his characters from the recesses of his memory.

Cinematic Adaptation: My friend, writer and film director Frank Darabont (The Shawshank Redemption, The Green Mile) once told me that Ray Bradbury has never been properly served on the screen. Frank felt that none of the major commercial cinematic adaptations of Ray Bradbury’s work were exceptional films. And I agree with him. The 1983 adaptation of Something Wicked This Way Comes is likely the best of the lot. But there are a few small, independent short films based on the work of Bradbury that are fantastic achievements. In 2011, the independent filmmaking company, Beverly Ridge Pictures, produced a remarkable adaptation of “The Small Assassin.” I was proud in 2005 to connect the filmmakers directly to Ray. When he finally saw it, he loved every second of it.

#19 “THE TOYNBEE CONVECTOR”

Where to Find It: The Toynbee Convector, Bradbury Stories

First Published: Playboy, January 1984

Plot Synopsis: As the world becomes increasingly rife with war, political crises, environmental destruction, disease, despair, and “incipient nihilism” (sound familiar?), Craig Bennett Stiles, a 130-year-old time traveler, returns to the present day after traveling to the future. And he has good news. The world has corrected its ways. Things are utopian in the future. This message of hope prompts the citizens of the present to create the better world foretold by the time traveler.

Spoiler Alert: As it turns out, the time traveler’s story was all a hoax, a fable of smoke and mirrors, as a way to prompt modern society out of its downward spiral of self-destruction.

Critique: This story is the most contemporary tale on my list of 25 “Essential Bradbury” short stories. There is simply so much top-shelf Bradbury crafted during his early forays into horror (1942-1947), and, then, in his golden era (1947-1962), the competition is just too robust. This is not to discount later Bradbury works such as the minor masterpieces Green Shadows, White Whale and From The Dust to Returned. But it’s darned near impossible to stand toe-to-toe with 1940s and 1950s Bradbury.

“The Toynbee Convector,” the title story from Bradbury’s 1988 collection, is certainly not even Bradbury’s finest prose. But several things elevate this story, helping it land on this esteemed list.

Ray Bradbury was a magician with metaphors. His best writing is awash in profoundly evocative, figurative language, allowing the reader to see, feel, and sense the story in ways that are completely singular to the author.

I asked Ray Bradbury about his use of metaphor in my book, Listen to the Echoes: The Ray Bradbury Interviews:

“You know why the teachers use me? I speak in tongues. I write metaphors. Every one of my stories is a metaphor you can remember. The great religions are all metaphor. We appreciate things like Daniel, the lion’s den, you know. People remember these metaphors because they are so vivid you can’t get free of them, and that’s what kids like in school. They read rocketships and encounters in space, things with dinosaurs, Something Wicked with strange carnivals—you know, all these things. I think I just naturally latch on to them. All my life, I’ve been running through the fields and picking up bright objects. I turn it over and say, “Hey, there’s a story.”

Bradbury had a mastery of metaphor that was, without question, one of his great strengths as a writer. There was the metaphor rich language within his stories, but also the larger, central metaphors of the individual tales themselves, which can also be looked as allegories. “The Toynbee Convector” is just such an allegory. Craig Bennett Stiles is a stand-in for Bradbury himself, who creates illusions in his writing. Bradbury often said he wrote “cautionary tales,” and in “The Toynbee Convector,” the “time traveler” cautions us that we have the power right now to repair the future. Ray Bradbury is often associated with dystopian fiction because of his opus, Fahrenheit 451. But the “Toynbee Convector” is a rare sojourn into utopian speculative fiction, where the ever-wise Ray Bradbury instructs us that we alone have the wherewithal to create our future, but we must act now. Bradbury is often deemed a visionary, and this later story from his canon is a fine example. “The Toynbee Convector” is perhaps more relevant today than ever before.

Late Night Confession: One night, very late, Ray and I were returning back to his home after seeing one of his plays and then dining in Beverly Hills. We climbed in the back of his town car (Ray never drove an automobile) and Ray turned to me with an admission.

“As you know,” he said, “when people ask me if I have a favorite story of own, I tell them they are all my children and you must not choose favorites.”

But then Ray looked at me very seriously and said, “But I think ‘The Toynbee Convector’ may well be my favorite. I think it is one of my best.”

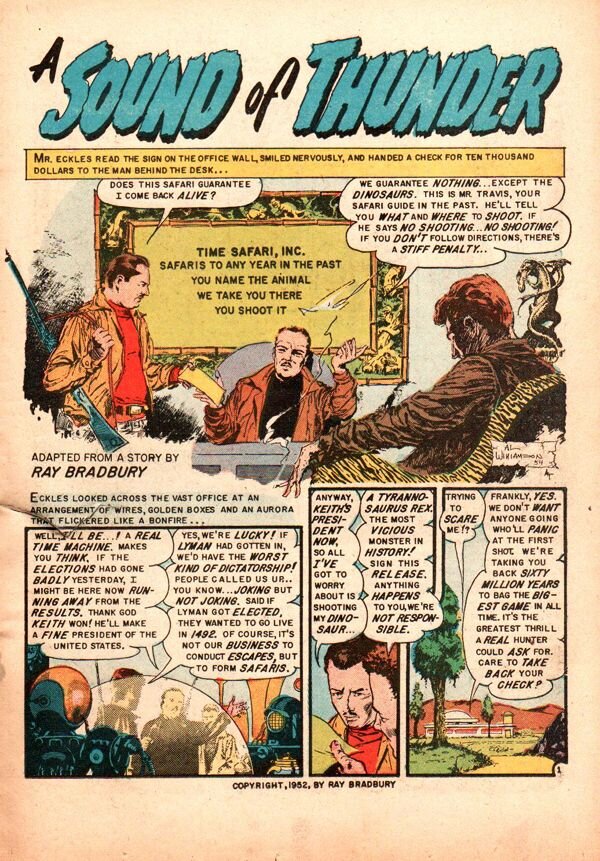

#18 “A SOUND OF THUNDER

Where to Find It: The Golden Apples of the Sun, The Stories of Ray Bradbury

First Published: Colliers, June, 1952

Plot Synopsis: A group of adventurers travel back in time to hunt the most dangerous game—the Tyrannosaurus Rex. The caveat? Don’t mess with anything else. Dinosuars will become extinct, the hunters are warned. Tamper with other things and, well, it’s called the “Butterfly Effect” for good reason.

Anecdote: You write a short story about one of your great childhood loves. Dinosaurs. The story is a time-travelling thrill ride with a description of the T-Rex that no CGI could ever come close to depicting. And when your story is done, your very premise of a time-traveling hunter stepping on a butterfly becomes part of our cultural vocabulary. AMAZING.

That Description of the T-Rex:

It came on great oiled, resilient legs. It towered thirty feet above half of the trees, a great evil god, folding its delicate watchmaker’s claws close to its oily reptilian chest. Each lower leg was a piston, a thousand pounds of white bone, sunk in thick ropes of muscle, sheathed over in a gleam of pebbled skin like the mail of a terrible warrior. Each thigh was a ton of meat, ivory, and steel mesh. And from the great breathing cage of the upper body those two delicate arms dangled out front, arms with hands which might pick up and examine men like toys, while the snake neck coiled. And the head itself, a ton of sculptured stone, lifted easily upon the sky. Its mouth gaped, exposing a fence of teeth like daggers, its eyes rolled, ostrich eggs, empty of all expression save hunger. It closed its mouth in a death grin. It ran, its pelvic bones crushing aside trees and bushes, its taloned feet clawing damp earth, leaving prints six inches deep wherever it settled its weight. It ran with a gliding ballet step, far too poised and balanced for its ten tons. It moved into a sunlit arena warily. Its beautifully reptile hands feeling the air.

Critique: “A Sound of Thunder” is Bradbury at his speculative best. A perfect fusion of idea, language, description, and high entertainment, the story tackles the very premise of how mankind’s smallest actions can have universal implications.

Anecdote: When I would visit Ray Bradbury at his home in Los Angeles, particularly in the late years when his health was waning, he would ask me to fetch books from his shelf and read them aloud.

“Read that paragraph from ‘A Sound of Thunder,’” he often asked. “The one that describes the dinosaurs.”

And I would read the paragraph and, when I was done, look up at Ray. Tears would be streaming down in his cheeks.

“I can’t believe I wrote that,” he said. “I am so grateful.”

#17 “POWERHOUSE”

Where to Find It: The Golden Apples of the Sun, The Stories of Ray Bradbury

First Published: Charm, March 1948

Plot Synopsis: A woman, alongside her husband, travels by horseback to visit the bedside of her dying mother and is forced to seek shelter from the rain inside a remote electrical power station. Spending the night in the utility structure, the woman has a transcendental awakening.

Backstory: Ray Bradbury on “Powerhouse” from Listen to the Echoes: The Ray Bradbury Interviews:

“I lived next door to an old powerhouse when I was in Venice [California] in the early 1940s. I used to go out at night and just stand there, listening to the machinery. It was very simple. The hum of all of that tremendous equipment was a religious hum to me. And that hum said things to me and stirred up my soul. So, I went and wrote the short story, all because that old powerhouse hummed at me.”

Critique: My students tend to have mixed feelings about this story. Half seem to love it, the other half appear ambivalent. As this list is utterly subjective, I include it here as one my very favorites. “Powerhouse” showcases another dimension to Bradbury—that of the realist prose stylist. The sole fantastic element of the story is the spiritual epiphany of the story’s protagonist. Quiet, atmospheric, awash with rich Bradburian description, “Powerhouse” exemplifies the breadth of the Bradbury canon. Signifying its literary accomplishment, the story was a runner-up for the vaunted O. Henry Memorial Prize for short fiction in 1948. This story is quiet, beautiful Zen meditation on how we all connect to the universe.

Footnote: The original red brick Los Angeles Bureau of Electricity station that inspired Bradbury to write this story still stands (even though the former Bradbury residence next door has been raised). Fans can find the location at 670 South Venice Boulevard in Venice, California.

#16 “CALLING MEXICO”

Where to Find It: Dandelion Wine (as an untitled story); The Stories of Ray Bradbury

First Published: August 5, 1950, Colliers (published as “The Window”).

Plot Synopsis: Colonel Freeleigh, a wheelchair bound elderly man, very late in his days, dials the telephone, calling a friend in Mexico City. He asks him to open the window so he might hear the beautiful street sounds so far, far away, all the traffic, and the vendors and the voices. This is how the elderly man is able to connect to the outside world and feel alive.

Critique: “Calling Mexico” is emblematic of many of the themes inherent to Dandelion Wine, most notably, loss of innocence, time, and mortality. The story begins with Ray Bradbury simultaneously brandishing two of his primary literary weapons: metaphor and use of poetic language. Colonel Freeleigh wakes after dreaming he is the last apple on a tree, clinging to its branch, at last surrendering and falling into darkness.

And then there is that day when all around, all around you hear the dropping of the apples, one by one, from the trees. At first it is one here and one there, and then it is three and then it is four and then nine and twenty, until the apples plummet like rain, fall like horse hoofs in the soft, darkening grass and you are the last apple on tree; and you wait for the wind to work you slowly free from your hold upon the sky, and drop you down and down. Long before you hit the grass you will have forgotten there ever was a tree, or other apples, or a summer, or green grass below. You will follow in darkness…

Colonel Freeleigh lives for the moments when a group of boys visit him, so he can transport them with his stories of old. But then, when his doctor cautions that the visits are causing him too much excitement, the Colonel turns to another ritual of magical transportation—the telephone. He picks up his phone and dials a friend in Mexico City where he asks him to hold the receiver out the window so he might listen to the sounds of the city thousands of miles away.

In “Calling Mexico,” as with many stories in Dandelion Wine, Bradbury examines the narrative tropes of science fiction and fantasy, in this instance teleportation and time travel, through the wonder of the everyday. In typical Bradburian philosophy, the author is telling us that we don’t need transporters and time machines to achieve the fantastic, a everyday device like a telephone, and the act of storytelling are, in their own way, miracles straight out of science fiction.

Personal Aside: It’s difficult not to see the bittersweet irony in the premise of “Calling Mexico.” Bradbury wrote the story in his late twenties, not far removed from his own halcyon boyhood. But in his last years of life, a nonagenarian, Ray Bradbury spent most of his time at his longtime Los Angeles home, mostly in bed, his strength fading with each passing day. He was well aware that he was no not as much Douglas Spaulding, the young protagonist in Dandelion Wine, but, instead, he was Colonel Freeleigh. He knew as his lifelong friends Forrest J Ackerman and Julie Schwartz (as well his brother Skip and wife Maggie) had passed on, that he was now, indeed, that last apple on the tree.

Bradbury as Time Machine: One of the points I made in my book Listen to the Echoes: The Ray Bradbury Interviews was that Ray Bradbury lived during a time of the greatest technological achievement humankind has ever witnessed. Proving the point, when Bradbury was a boy, growing up in Waukegan, Illinois in the 1920s, he encountered surviving veterans of the Civil War. Later, when he became a globally renowned author, he befriended many of the astronauts from the Mercury and Apollo space programs. From the veterans of Bull Run, to the veterans of the Sea of Tranquility, Ray Bradbury was, in his own way, a living time machine.

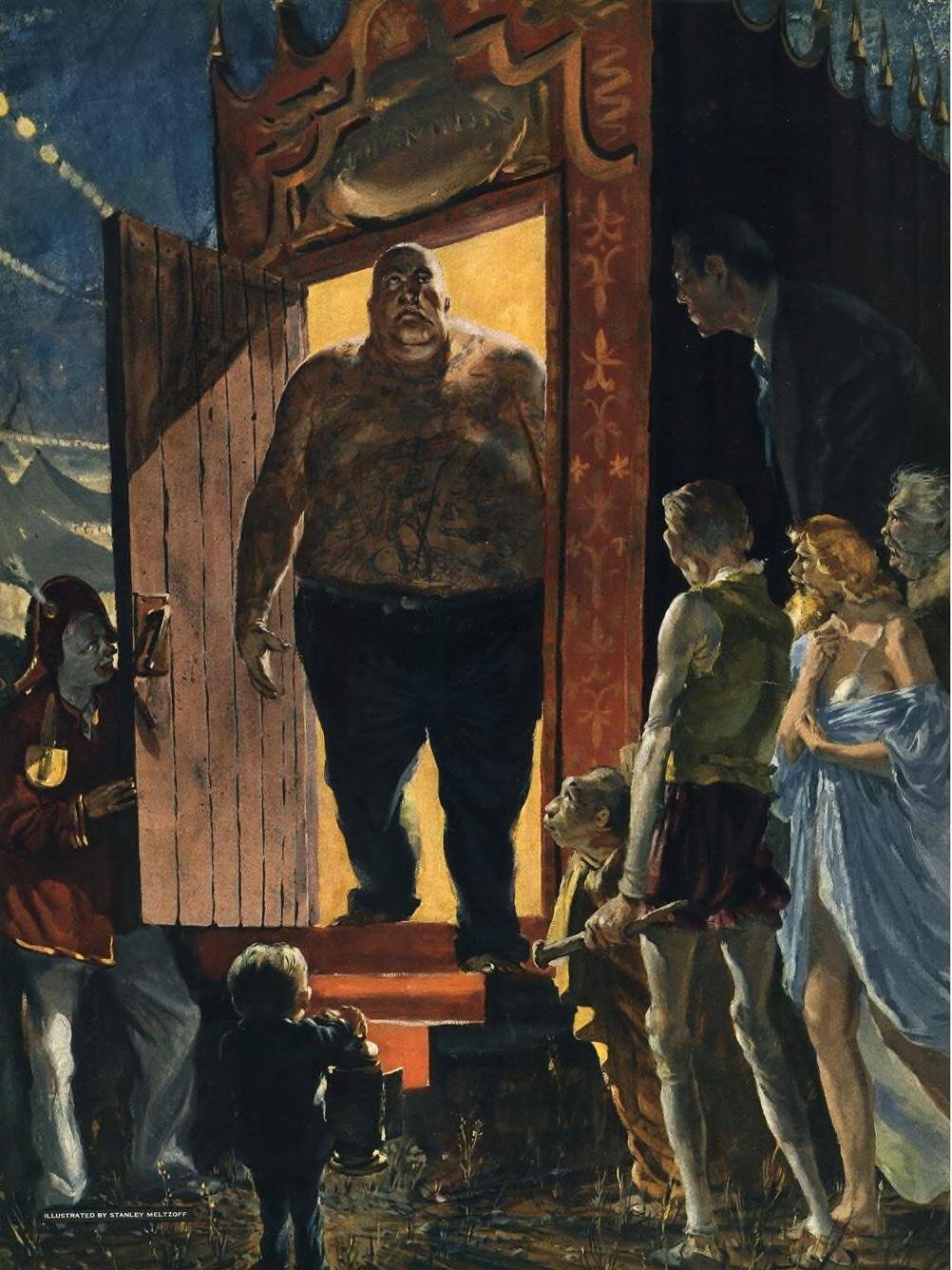

#15 “THE ILLUSTRATED MAN”

Where to Find It: The Vintage Bradbury, Bradbury Stories

First Published: Esquire, July 1950

Plot Synopsis: This story tells the shocking and tragic narrative of Mr. William Philippus Phelps and the witch in the dark woods of Wisconsin who turned him into “The Illustrated Man.” Phelps’ body is covered head-to-toe in skin illustrations that move and shift, displaying frightening stories if you look at them closely. This is the little-known origin story of the iconic title character behind Ray Bradbury’s 1951 classic collection, The Illustrated Man.

Critique: This story could have easily fit into Bradbury’s first collection of Gothic horror and fantasy, 1947’s Dark Carnival, and it’s ironic that it was not included in Bradbury’s book of the same name, The Illustrated Man, four years later. While the concept of the tattooed man and his skin illustrations provided a brilliant framework for the collection (each tattoo is a short story in the book), the title story was a work of fantasy and horror, while the rest of the tales in The Illustrated Man are dark and wildly imaginative visions of a science fictional future. As a result, the origin of how the Illustrated Man became this hideous creature with tattoos that moved across his body was never included in the book of the same name. The story was an Esquire magazine favorite, and for good reason. It is also a rare example of a character’s backstory in the Bradbury universe getting its own story. Imagine—Captain Beatty’s origin? Mr. Dark’s early years? But an equally enigmatic character in this creepy tale is the witch in the woods who tattoos the Illustrated Man and destroys his life as result. Bradbury’s description of the witch who leaves these horrible tattoos on the body of Phelps is pure, poetic Bradburian grotesquery:

Inside the door was a silent, bare room, and in the center of the bare room sat an ancient woman. Her eyes were stitched with red-resin thread. Her nose was sealed with black-wax twine. Her ears were sewn too, as if a darning-needle dragonfly had stitched all her senses shut. She sat, nit moving, in the vacant room. Dust lay in a yellow-flour all about, unfootprinted in many weeks; if she had moved it would have shown, but she had not moved. Her hands touched each other like thin, rusted instruments. Her feet were naked and obscene as rain rubbers, and near them sat vials of tattoo milk—red, lightening-blue, brown, cat-yellow. She was a thing sewn tight into whispers and silence.

Only her mouth moved, unsewn: “Come in. Sit down. I’m lonely here.”

“The Illustrated Man” is Bradbury at his Gothic best. The story lends even more sympathy for the tragic title character than we get in the short interludes in the collection of the same name.

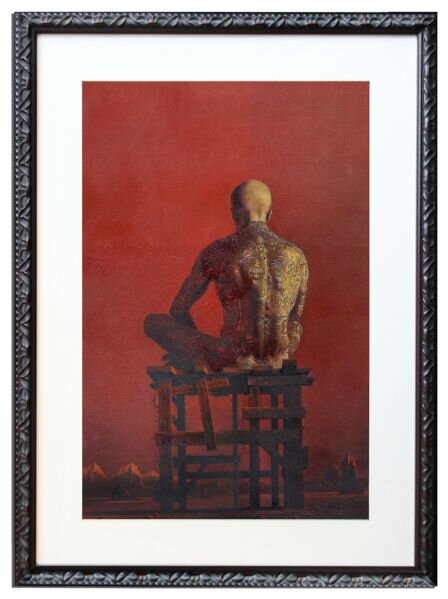

Personal Aside: As mentioned briefly in #24 on this list, The Illustrated Man was the first Bradbury book I discovered when I was eleven. On the cover of that frayed paperback book—a 1969 Bantam edition— was a striking painting by artist Dean Ellis. I stared at the cover endlessly, a molten red landscape with the Illustrated Man seated on a makeshift wooden pedestal of splintered wood and nails, his tattooed back to us. I was changed forever. Bradbury had tattooed my heart.

Decades later, the first time I walked into Ray Bradbury’s Los Angeles home on Memorial Day Weekend 2000 to interview him for the Chicago Tribune Magazine, I entered the home and saw it. Just inside the entryway to the left of the front door. It was the painting. The original 17” x 26.5” cover painting by Dean Ellis I had marveled at as a child.

I closed my eyes for a moment. I had arrived in Oz.

#14 “THE NEXT IN LINE”

Where to Find It: The October Country, The Stories of Ray Bradbury

First Published: Dark Carnival

Plot Synopsis: A young American married couple traveling deep into Mexico is forced to overnight in the colonial town of Guanajuato. After visiting the catacombs that house the infamous “Mummies of Guanajuato,” the wife grows increasingly distrustful of her spouse and begins a decent into paranoia, fear of death, and becoming the next body to be put on display.

Backstory: In the autumn of 1945, Ray Bradbury traveled with his friend Grant Beach by automobile through the jungles and the small towns of Mexico. The friends visited the real life underground tomb that houses the bodies of the exhumed whose families failed to pay their cemetery dues. Bradbury was forever scarred by the images of the deceased, strung up and put on display. Strangely, because of soil conditions in the region, the bodies had been naturally preserved.

Critique: I asked Ray Bradbury once what, in his mind, was the scariest story he ever wrote. His answer was “The Next in Line.” Bradbury’s approach to the psychology of fear adhered to the “less is more” philosophy. That is, what is not seen is often far more frightening that what is. One of my students recently referred to this as “the zipper effect,” when a movie monster comes on screen and the audience can readily see the zipper in the suit. Bradbury always believed that Hitchcock had it right. “Fear is far more effective when it is like Chinese water torture,” he told me, “employed slowly, one drop at a time.”

“The Next in Line” was the last story Bradbury wrote for his first collection, 1947’s Dark Carnival. It is also the longest tale in the book and his most psychologically nuanced up until that point in his publication history. The story addresses the multiple themes of marital discord and trust, fear of dying, and isolation and loneliness. The decent into madness Marie experiences, reflects the madness inherent in so much of Bradbury’s own literary influence, Edgar Allen Poe. The story is awash in death imagery, from coffins, to catacombs to candy Day of the Dead skulls. And as so much of Bradbury is culled from real-life experience, I am certain that the married couple is a reflection of Ray’s relationship with his friend Grant Beach (Bradbury dedicated Dark Carnival to Beach). As the friends traveled through Mexico, they bickered continuously, their relationship unraveling to the point that, on their return home, Grant Beach tossed Ray Bradbury’s typewriter into a river.

Along with “The Small Assassin,” “The Next in Line” is one of Ray Bradbury’s most psychologically horrific tales.

#13 “THE PEDESTRIAN

Where to Find It: The Golden Apples of the Sun, Bradbury Stories

First Published: The Reporter, August 7, 1951

Plot Synopsis: Leonard Mead, a resident in an unnamed city in the year 2053, takes long walks each night and never encounters any other pedestrians. He is the only one savoring the night, outside in the fresh air, away from his electronic devices, gaining a form of freedom, when a self-driving police car pulls up to arrest him for his activities.

Backstory: As Ray Bradbury often told the story, it was a late, windy autumn night in late 1940s Los Angeles, the Santa Ana breeze carrying the scent of cinders. Ray and a friend had finished dinner at a restaurant in the mid-Wilshire district of Los Angeles and were walking to a bus stop, deep in conversation. (Neither man owned an automobile.) As he walked, Ray munched on some soda crackers, a box of which, in his typically eccentric fashion, he had brought with him to and from the restaurant. A police car wheeled up beside them. An officer stepped out and approached the two men. He asked what they were doing.

“Putting one foot in front of the other,” said Ray, his mouth full of crackers.

Displeased, the officer asked again what they were doing.

“Breathing the air,” said Ray, “talking, conversing, walking.”

As Ray spoke to him, bits of cracker flew from his mouth, dusting the police man’s uniform. The officer flicked the crumbs from his chest and shoulders.

“It’s illogical, your stopping us,” Ray continued. “If we wanted to burgle a joint or rob a shop, we would have driven up in a car, burgled or robbed, and driven away. As you see, we have no car, only our feet.”

The police officer was skeptical of the two men out late walking in a city not known for foot traffic. He also took with Ray Bradbury as a smart-ass. (In actuality, Ray was just being Ray, innocently impudent, a little naïve.)

As Ray recalled it, the officer was somewhat adjutated.

“Walking, eh?” he said. “Just walking?”

Ray and his friend nodded, wondering if they were the victims of some sort of prank.

“Well,” the officer said, “don’t do it again!”

The officer returned to his patrol car and drove off into the night.

Incensed, Ray went home and wrote “The Pedestrian,” a story about a future society where walking is forbidden and all pedestrians treated as criminals.

Critique:

“The Pedestrian” is one of Ray Bradbury’s earliest forays into dystopian fiction. This satirical look at a near-future world where a media-addicted populace no longer takes simple, reflective walks, inverts the societal norms of our present times and posits their total disappearance. People in the year 2053 no longer walk anywhere. Ray Bradbury extrapolated his own experience with the police officer (and his broader observations of the demise of walking culture in Los Angeles) and examined it through the genre of science fiction. What would happen if walking was illegal? Why would it be outlawed? Most science fiction revolves around the “what-if” premise, and here the author ponders, what if people stopped walking places?

But perhaps most important about “The Pedestrian” is that it directly led Bradbury to writing Fahrenheit 451. Two years after the publication of “The Pedestrian,” Bradbury took another character out for a walk in a lonely, tech-dependent world, this time a fireman named Guy Montag who burns books for a living. On a walk after work, he encounters another pedestrian, Clarisse McClellan and the novel begins…

With “The Pedestrian,” Ray Bradbury was experimenting with the central themes and ideas of Fahrenheit 451: the proliferation of mass media as a societal opiate; the ostracization of the individual for participating in what are deemed “regressive” activities, and, of course—censorship.

Metaphor Alert:

Bradbury refers to automobiles seen from a distance as “Beetles,” a metaphor he used in his 1947 short story “Jack-in-the-Box” and again in Fahrenheit 451. He obviously liked this description!

#12 “THE DRAGON”

Art inspired by the Ray Bradbury story “The Dragon,” by Pasha K.

Where to Find It: A Medicine for Melancholy, R is for Rocket, Bradbury Stories

First Published: August 1955, Esquire

Plot Synopsis: Two knights, crossing a grassy moor at midnight, are on a quest to slay a dragon that has been devouring men who try to defeat it. They wait in the night for the great beast, described in the story as follows:

“His breath a white gas; you can see him burn across the dark lands. He runs with sulfur and thunder and kindles the grasses.”

The twist to this story (SPOILER ALERT) is that there has been some crease in time and the knights exist in the same realm as locomotives. The beast is a train passing through the moor.

Story Origins: Here is an incredibly cool tip for writers direct from the sensei himself: Early on in my relationship with Ray Bradbury, we were sitting at his dining room table eating carry out Chinese food. The table, purchased the week Ray and Maggie Bradbury were wed in 1947, was, effectively, now a desk piled impossibly high with mail, manuscripts, and plastic milk crates (Ray’s ad hoc filing system) loaded with Bradburiana. The phone rang. It was a call from a fan.

Let me stop for a moment and elaborate: when I travel and lecture about Ray Bradbury at colleges, universities and libraries around the world, people always come up to me and share stories about writing to Ray Bradbury and he actually wrote them back. These letters written by the man himself, not by an assistant. People regularly bring these letters to my events to show me. Sometimes they are framed. Sometimes they clutch them close to their hearts. Sometimes I can see tears in their eyes as they share these keepsakes. This is always incredibly meaningful to me. Seeing Ray’s words, seeing his sentiments, knowing that he had held these letters in his hands, and likely mailed them out himself, it makes him feel alive again.

Ray Bradbury always had a very special relationship with his fans. He made himself unusually accessible. He was as appreciative of his readers as they were of him. So, at least when I worked with him, he would spend a few hours each morning responding to fans. “When someone writes you a love letter,” he once told me, “you have to respond!”

Bradbury’s communication occasionally extended beyond letter writing. Sometimes he would speak to fans by phone. And on this day, a fan he had been corresponding with called him as I was sitting there at his dining room table. In his advancing years, Bradbury’s hearing had diminished and the volume on the phone was always cranked up. I could hear the caller on the other end of the line. After an exchange of pleasantries, the caller, a young male writer, told Bradbury that he was having some difficulty coming up with new ideas. Bradbury gave him some quick advice: “Make a list of ten things you love” he instructed, “and write a short story, a poem, or an essay about each one of them.” He then told the young writer to call him back after he had completed the assignment.

This simple prescription was vintage Ray Bradbury. Writing about the things he loved was paramount, he maintained, to his own success. An example he often used to prove this point? He loved dinosaurs as a child and wrote a dinosaur story as an adult (“The Fog Horn”) that prompted film director John Huston to hire him to write the screenplay for Moby Dick. This was his entry into Hollywood and, for the first time, financial security in his life.

Dinosaurs. Mars. Halloween. His hometown. Libraries. Ray Bradbury often wrote about the things he loved. He followed the advice he gave to the young writer. And Ray Bradbury was always in love with trains, too. As a child, he would lie in bed at night in his home at 11 South Saint James Street in Waukegan, Illinois and listen to the lonely sounds of locomotives passing far out west of town. Ray and his older brother Skip would wake before sunrise to watch the circus trains lumber into town and unload their mysterious passengers and their great animal performers.

As an adult, Ray did not fly on an airplane until he was 62. He took passenger trains and he loved each and every adventure. He wrote about this love in the 1968 Life magazine essay, “Any Friend of Trains is a Friend of Mine.”

Bradbury took his love for trains and his mastery of simile and metaphor to the writing of “The Dragon.” With the idea that a train would be perceived as a monster, or a mechanical beast to people long ago, Bradbury had his basic premise for writing “The Dragon.”

Critique: There is good reason that Bradbury selected this story to include in his 1962 collection for young adult readers, R is for Rocket. The metaphor of the train as the beast back in time is a clear example of Bradbury as modern mythologist. The very idea of the story is an original mythic concept. As Bradbury grew as a writer, he began to recognize the timeless quality of narrative metaphor. Like many great Bradbury short stories, “The Dragon” may be light on characterization at the expense of idea, but it doesn’t lessen the overall impact of this mythic tale.

With “The Dragon,” Bradbury envisions the technological future (the train) perceived through the eyes of the past (the knights setting out to slay the beast). This is a classic example of Bradbury looking at the perception of reality, in this case the knights attacking a dragon that is, in actuality, a locomotive from the future. Both the knights and the train are lost in time, intersecting, somehow, on the same plain, a classic battle of the past versus the future, a common thread in Bradbury’s thematic modus operandi.

The Point of View Shift Ending: Ray Bradbury was a master of short story endings. Writers learn this only from finishing stories, and Bradbury finished (and published) dozens and dozens of short stories in the first two decades of his writing career. As the great Neil Gaiman once said (himself, a Bradbury acolyte), “Whatever it takes to finish things, finish. You will learn more from a glorious failure than you ever will from something you never finished.”

Bradbury had many tools in his story-ending arsenal. One was a trick he employed in stories such as “The Small Assassin,” “The Next in Line” as well as in “The Dragon.” The endings of these three stories, along with a few others, switch point-of-view on the last page. In “The Dragon,” the story is told in a close, omniscient third person. We see the story over the shoulders of the knights on their quest. And then, at the end of the story, we seamlessly switch to inside the locomotive, and the point-of-view of the engineer and the coal-man inside the train who saw the knights charging at them with their lances. This point-of-view switch at the end of stories is just one of Ray Bradbury’s slight-of-hand techniques to ending his short stories.

#11 “THE ROCKET MAN”

Where to Find It: The Illustrated Man, The Stories of Ray Bradbury

First Published: March 1, 1951, MacLean’s

Plot Synopsis: A father leaves for months at a time to work in space as a “Rocket Man.” His wife and son stay home alone, worried about the profound dangers of his occupation. The dad only returns for a few days, and then he is off again. His son yearns to grow up to be just like his father, but begins to recognize the deep, innate calling of his Dad’s occupation, juxtaposed with his profound desire to be home with his family. The father doesn’t want this life for his boy, and promises that each trip will be his last. But will it?

Critique: Bradbury penning top-tier humanist science fiction—what’s not to love? While the vast majority of golden era SF scribes were focusing on thrusters, anti-gravity, and all manner of tech-plausibility, Ray Bradbury saw the genre of science fiction as another way of examining what it means to be human. Bradbury saw the genre as a vehicle to coyly comment on contemporary culture, to tell stories drenched in the human condition. He used genre fiction to write literature. “The Rocket Man” beautifully and simply uses the genre of science fiction to look at life/work balance, and does it with typical Bradburian poetic prose and melancholy results. Here we have the classic tale of the sea-faring adventurer, or the soldier going out for one more deployment, but this tale is set, instead, in the deeps of space.

Bradbury Rocks: As a Gen-Xer, I was always aware of the pop legend that this story was the inspiration for the 1972 Elton John classic, “Rocket Man.” When I was in the throes of working on my book, The Bradbury Chronicles: The Life of Ray Bradbury, I wrote to Bernie Taupin, Elton John’s longtime collaborator and lyricist, and asked about the Bradbury connection. He wrote back with the following, confirming Bradbury’s influence:

“The idea of a futuristic society where an astronaut was a routine job, something as tedious as a long-distance truck driver was fascinating, psychedelicize this with some drug culture references and a little peripheral esoteric mumbo jumbo and presto. My main goal, however, was to project a sense of the overwhelming loneliness space offers us; in this I think we succeeded.”

Adding to the pop culture meta-weirdness of it all, William Shatner hosted the 1978 Saturn Awards (the Oscars of Sci Fi, Fantasy, and horror) and delivered a trippy spoken word version of the Elton John song (Shatner was introduced by Bernie Taupin). This little morsel of Shatnerian schmaltz-brilliance has become a bona fide cult classic. After Ray passed away in 2012, I hosted a memorial at Comic Con in San Diego that included appearances by Joe Hill, Rachel Bloom, George Clayton Johnson and others. I asked William Shatner if he would, perhaps, reprise his epic ’78 performance of “Rocket Man,” but he politely declined. Once was enough.

#10 “THE HOMECOMING”

Where to Find It: The October Country, The Stories of Ray Bradbury

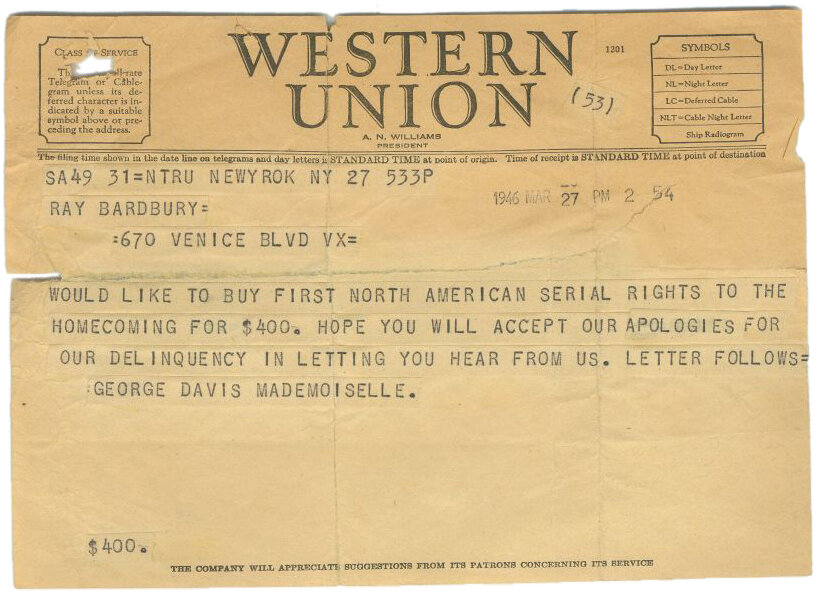

The original telegram acceptance from Mademoiselle magazine editor George Davis to Ray Bradbury (with the charming misspelling of “Bardbury”.

First Published: Mademoiselle, October 1946

Plot Synopsis: A foundling human child is raised by a family of lovable monsters. As the extended family gathers at their rococo Northern, Illinois mansion for an All Hallows reunion, Timothy, lacking supernatural powers, feels like an outcast.

Critique: Bradbury wrote this story while in his mid-twenties, yet he was already well on his way to taking traditional genre fiction into uncharted wilderness. Originality of story, combined with narratives always steeped in humanity, all told in a poetic style, were fast becoming the hallmarks of the writer. “The Homecoming” is an allegory for Bradbury’s own childhood, when he himself felt the part of the misfit, the outsider, even as he was surrounded by a loving and doting extended family. The child as outsider is a theme Bradbury would continue to examine, but never again with such delightfully gothic aplomb.

Anecdote: The story behind the publication of “The Homecoming” is legendary. Bradbury submitted the story to the pulp magazine Weird Tales and it was promptly rejected. The editor wanted a more traditional horror story. Bradbury’s originality was now coming back to hinder him in the pages of the pulps. On a whim, he decided to submit the tale to Mademoiselle, a well-respected slick publication that published literary fiction. An office boy discovered the story in the voluminous slush pile and brought it to the attention of fiction editor Rita Smith (sister of author Carson McCullers). Mademoiselle not only published the story, the editors shifted the entire tone and look of the October, 1946 issue to have a Halloween theme, with Bradbury’s story at the center. New Yorker artist Charles Addams was brought on to paint the accompanying art. And the office boy who first eye-balled the tale in the submission pile? Truman Capote.

“Homecoming” in the October, 1946 issue of Mademoiselle, with art by the great Charles Addams.

#9 “I SEE YOU NEVER”

Where to Find It: The Golden Apples of the Sun, The Stories of Ray Bradbury

First Published: November 8, 1947, New Yorker

Plot Synopsis: The tale of a Mexican immigrant in Los Angeles who is deported back to his homeland.

Backstory: This elegiac tale is based on a real-life incident in Ray Bradbury’s life. One afternoon in the mid-1940s while having lunch at the tenement building owned by his friend Grant Beach’s mother, one of the building’s tenants came to the door, escorted by the county sheriff. He was being deported back to Mexico. As Ray Bradbury was sitting there having lunch, he heard it: “I see you never, Mrs. Beach. I see you never.” With those four poetic words, Bradbury went off to write his story.

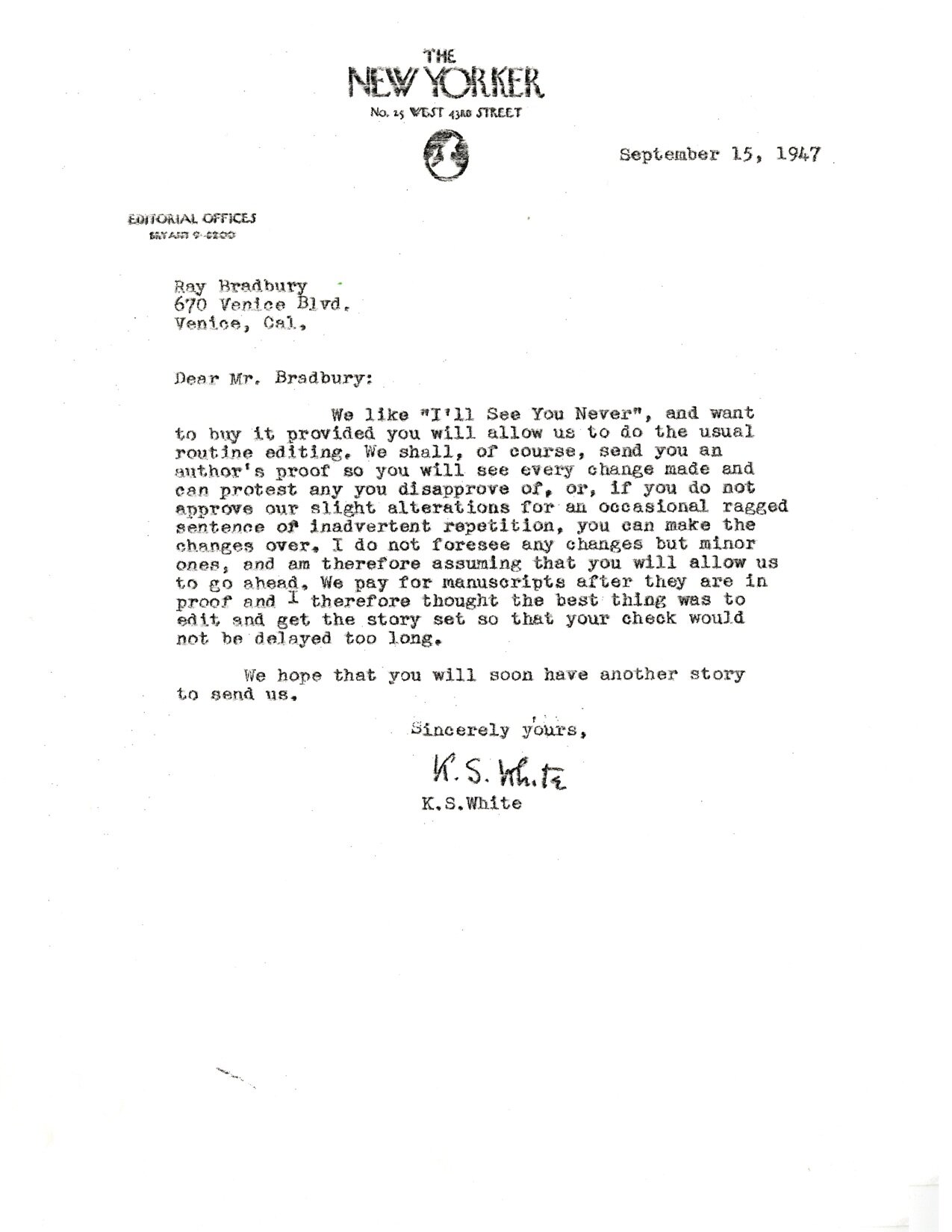

The acceptance letter from New Yorker editor, K.S. White (wife of author E.B. White) to Ray Bradbury for his story, “I See You Never.” (From the collection of Sam Weller)

“I See You Never” sold to the New Yorker on September 15, 1947, just twelve days before Ray Bradbury wed Marguerite McClure. The acceptance letter [pictured here] came from K.S. White, wife of noted author, E.B. White. And while the letter hints at a blossoming relationship between the then 27-year old writer and the most vaunted of literary publications, the story would be the only sale Bradbury would ever make to the magazine.

Critique:

“I See You Never” showcases the breadth of Bradbury’s storytelling abilities. He is, by no means, strictly a fantasist or Sci-Fi writer. The tale is straightforward, contemporary realist prose with nary an element of fantasy to be found. The conclusion is heart wrenching and, given the era in which it was published, a prophetic vision of the immigrant controversy that vexes American society to this. “I See You Never” was one of Bradbury’s earliest explorations into social issues. It is also illuminated Bradbury as the visionary he would soon become. He would, in a matter of just a few years, take his social concerns into works of fantasy and science fiction, with The Martian Chronicles and Fahrenheit 451.

#8 “ALL SUMMER IN A DAY”

Where to Find It: A Medicine for Melancholy, The Stories of Ray Bradbury

First Published: The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, March, 1954

Plot Synopsis: A group of viscous schoolchildren on the planet Venus (Hey, this is Bradbury) lock a little girl named Margot in a classroom closet just as the sun is about to make its once-every-seven years appearance. Margot used to live in Earth and she has seen the sun before and that makes her classmates jealous. And mean.

Venus Aside: Ray Bradbury is known for his Mars stories. Hello? The Martian Chronicles? And after all, he only wrote two stories set on the second planet in our solar system. But both of these stories are on this esteemed list. When Bradbury was a child, Venus was a planet obscured by cloud cover. And so in Ray Bradbury’s imagination, Venus was a rain planet.

Critique: “You are My Sunshine” is a song from the popular American songbook, first recorded by country music artists, The Pine Ridge Boys, coincidentally, on Ray Bradbury’s 19th birthday, August 22, 1939. Of course, this song is now a staple of nursery school sing-a-longs. In Ray Bradbury’s tale, children literally attempt to take the sunshine away from a classmate. “All Summer in a Day” is a profound and tragic science fictional examination of school bullying, written in the early 1950s!

With the proliferation of cyber-bullying and teen bullies in 21st century America, Bradbury was a visionary yet again, looking at the subject LONG before it became tragic commonplace.

Story Origin: I once asked Ray Bradbury why he wrote this story. His answer?

“Because kids are mean!”

Bradbury himself was a victim of schoolyard bullies growing up in the 1920s in Waukegan, Illinois. He addressed this anguish in this absolutely classic tale.

Anecdotal Popularity: Ray told me frequently that, over the years, he was asked about this story more than any other story he ever wrote. His reasoning? “All Summer in Day” has been a staple of Language Arts classes for decades and the story deeply resonates.

#7 “MARS IS HEAVEN”

“Mars is Heaven” from Esquire magazine, December 1, 1950. Illustration by Lew Keller.

Where to Find It: The Martian Chronicles (as “The Third Expedition”), The Stories of Ray Bradbury

First Published: Fall 1948, Planet Stories.

Plot Synopsis: A rocket lands on Mars and when the astronauts open the hatch and descend, they discover an idyllic Midwestern town inhabited by all their deceased loved ones.

Critique: A masterful mash-up of S.F., fantasy, and suspense, the story, when first published, was a clarion call, trumpeting the beginning of the end of Bradbury’s career as a pulp fiction writer of note. While the tale may have been published in Planet Stories, it was a story of distinct quality, worthy of the magazines Bradbury was writing for at the time, such as Harper’s, the New Yorker, Mademoiselle, and others. With “Mars is Heaven,” in a single brush stroke, Bradbury hit on many of the themes that would quickly become his signatures: magic, loss, nostalgia, and fear of the unknown. The tale also showcased Bradbury’s mastery of slow-reveal suspense, where every sentence is a layer torn away, building towards the climax. “Mars is Heaven” is a cornerstone story in Bradbury’s Martian mythology, a tale where concept and execution intersected, resulting in one of his very finest.

“Mars is Heaven” from Weird Science #18. Illustration by Wally Wood.

Footnotes: "Mars is Heaven!" was selected in 1970 by the Science Fiction Writers of America as one the best science fiction short stories published prior to the creation of the Nebula Awards. This classic group of stories was published in The Science Fiction Hall of Fame Volume One, 1929-1964. The story was adapted to several different media including multiple radio dramatizations (Escape June 2, 1950; Dimension X, July 7, 1950 and January 7, 1951; X Minus One, May 8, 1955; and Future Tense, July 1976); television (The Ray Bradbury Theater, July 20, 1990) and comics, pictured right, (Weird Science #18, March–April 1953, illustrated by the renowned artist, Wally Wood.

#6 “THE WHOLE TOWN’S SLEEPING

Where to Find It: Dandelion Wine, Bradbury Stories

First Published: McCall’s, September 1950

Plot Synopsis: A woman walks with her girlfriends into town to see a Charlie Chaplain film. She ignores warnings of a serial killer at large and, after saying goodbye to her companions, takes a short cut to get home through a wooded ravine. Walking alone through the dark, primordial forest, she hears footsteps behind her. The woman quickly descends into a deep state of paranoia and terror, as she rushes to get home. Is someone really out there, or is it just her imagination?

Anecdote: “The Whole Town’s Sleeping” centers upon a fictional serial killer who calls himself “The Lonely One.” When Bradbury was a child, growing up in the 1920s in Waukegan, Illinois there was a cat burglar named “The Lonely One.” The thief left messages for police, taunting them, signing his notes using his nickname. The petty thief was never caught. The setting of “The Whole Town’s Sleeping” is also rooted in real life. Waukegan, Illinois has a deep ravine that cuts through town, opening out into Lake Michigan. This deep, subterranean world was a playground for Bradbury when he was a boy. The movie theater that the women attend in the story, “The Elite,” was the theater Bradbury frequented as a child. It was the Elite where Ray Bradbury first saw The Hunchback of Notre Dame starring Lon Chaney when he was three. He long pointed to this film as being highly influential in the development of his imagination.

Critique: “The Whole Town’s Sleeping” was first collected in Dandelion Wine, a book that, in my estimation, is a sort of structural sibling to The Martian Chronicles. Both books are really short story collections assembled to look like novels. Both books utilize short bridge chapters to link the stories into a unified narrative. Both books have well-known and popular stories that represent Bradbury at his pinnacle in different genres. In The Martian Chronicles, “Mars Is Heaven” has often been sited as one of Bradbury’s crowning science fictional achievements. The story was selected by the members of the Science Fiction Writers of America as one of the “Greatest Science Fiction Stories of All Time” in the collection, The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume I. “The Whole Town’s Sleeping” represents one of Bradbury’s very finest suspense stories. It encapsulates Bradbury’s theory on effective suspense and psychological terror. Bradbury has often told me that good suspense and effective horror must be drawn out and sustained, like “Chinese water torture,” as he describes it. In the Whole Town’s Sleeping,” the internalized fear experienced by Lavinia Nebbs as she makes her way home crescendos slowly. The story utilizes the journey through the ravine in the same way that Washington Irving used the forest as an allegory for fear and the unknown in his 1820 American classic, The Legend of Sleepy Hollow. In a more modern pop-cultural connection, Bradbury has always prescribed to the same theory of fear as Hitchcock: what is not seen is often far more frightening than what is seen and known. With this in mind, “The Whole Town’s Sleeping” is Bradbury at his finest, most masterful suspense writing. It also contains one of Bradbury’s finest surprise endings.

Personal Story: Over the years, I have collected vintage postcards of Waukegan, Illinois. I found the postcard (Pictured right) of the ravine and it was postmarked, “August 22, 1922,” — Ray Bradbury’s second birthday. I gave the postcard to Ray for his 82nd birthday. I remember when he first looked at it, he held it in his hands and then drew it close to his face and looked at it for a long while. Finally, he proclaimed, “I know that tree.” I was dumbfounded. “What?” I asked. And he went on to explain to me that he knew the exact location in the ravine that the postcard depicted. He told me how to find it. I was skeptical, to say the least. Did he really remember the fallen tree pictured in the card? And even if he did, he was recalling it from the late 1920s or early 1930s, from his childhood. The odds that the tree was still there were slim. A month later, I drove up to Waukegan from my home in Chicago. It was a warm, sunny summer day. I walked through the park that now bears Ray Bradbury’s name and down the steps into the ravine. I followed Ray’s directions, hiking north for a good long time along the side of the creek. Sun cascaded down through the trees. There was a chorus of insects and birds. And then I stopped, and, to my amazement, there it was, the tree. All these years later. Almost identical to the postcard from the 1920s. I never doubted Ray Bradbury’s memory every again.

#5 “KALEIDOSCOPE”

Where to Find It: The Illustrated Man, The Stories of Ray Bradbury

First Published: Thrilling Wonder Stories, October 1949

Plot Synopsis: A rocket crew experiences a catastrophic explosion onboard their ship, finding themselves cast out into space, going off in separate directions, yet still able to communicate to one another over helmet radios as they each come to terms with their inevitable fates.

Bradbury on the story: “I sat down at my typewriter and asked myself, what would happen if an explosion occurred on a rocket and all the astronauts on board became castaways?”

Critique: Bleak in its concept, Bradbury’s astronauts each have their own epiphanies regarding mortality as they drift off into the forever vastness of space. Anger, regret and acceptance are all examined amidst the chilling, absolute loneliness of outer space. Is there anything more lonely than drifting off, alone into the vacuum of the cosmos? Bradbury’s ability to unify the quickly separating and drifting astronauts via helmet radio is a seamless and artful experiment in characters communicating in dialogue while no longer physically together. The ending of the story, with the point-of-view shift to a country road on earth and a little boy seeing the astronaut Hollis reentering the atmosphere as a shooting star is a classic, exacting Bradbury metaphoric finale.

Anecdote: In the four years I worked on The Bradbury Chronicles: The Life of Ray Bradbury, I traveled from my home in Chicago to Ray Bradbury’s home in Los Angeles every two or three weeks. I took the first flight out on February 1, 2003. When I walked into the rental car agency, I looked up at the TV monitors. Fiery debris was streaking across a brilliant blue sky. The space shuttle Columbia had catastrophically burned up upon reentry into the Earth’s atmosphere. My first thought: Kaleidoscope.

When I arrived at Ray Bradbury’s house 30 minutes later, I found Ray waiting for me. He was seated in his big oversized leather chair. The television was on and he was watching the news reports of the shuttle disaster.

“Kaleidoscope,” I said.

He had tears in his eyes.

“By God, you’re right.” He said.

#4 “THE LAKE”

Where to Find It: The October Country, The Stories of Ray Bradbury

First Published: May, 1944, Weird Tales

Plot Synopsis: A young boy, building sandcastles with a golden-haired friend on a beach, watches as the little girl goes too far out in to Lake Michigan. There is a strong undertow that day and she is suddenly taken under. Her body is never found. Years later, now grown and married, the man returns to the town where he grew up and walks along the empty beach on a late summer day. He finds closure when the little girl from his distant past somehow returns.

Backstory: This is where it all begins. This is the story when a young Ray Bradbury discovered Ray Bradbury. It was 1942 and he was just 22 years old. Ray was visiting a dear friend in downtown Los Angeles, and brought a portable typewriter with him. He sat in his friend’s backyard where there was a tranquil Japanese garden. Ray typed the word “The Lake” at the top of a page of blank paper. He often did this, scribbling down nouns that bubbled up from his subconscious. He then followed whatever path the noun presented to him. He let the noun lead him to story. In this instance, he was soon typing furiously. Two hours later, he was done and there were tears in his eyes. He knew he had done something different; he had written a story that was neither imitative of his literary heroes, nor derivative. He had created something wholly original, from his heart. He had discovered his voice.

“I realized I had at last written a really fine story,” he recalled many years later. “The first in ten-years of writing. And not only was it a fine story, but it was some sort of hybrid, something verging on the new. Not a traditional ghost story at all, but a story about love, remembrance, and drowning.”

Critique: “The Lake” was anything but a formulaic “weird tale.” With this story, Ray had done something he had not done as a writer until that juncture. He had turned inward and explored his childhood memories of growing up in Waukegan, Illinois, and in doing so, he inadvertently tapped into a creative wellspring that would become one of his primary creative tools—"autobiographical fantasy.” Along with looking at his memory through the prism of the fantastic, the story was at once lyrical, sentimental, and haunting.

Boom. Ray Bradbury discovered himself.

Adding to this vital creative discovery, with “The Lake,” Bradbury also landed on another all-important revelation. Just as Conan Doyle took ownership of Victorian London, or O’Conner put a flag down in the Gothic South, Ray Bradbury, with this single story, would make a claim to the Midwest autumn as his milieu. And as the years and publications continued, he would make a formidable case that he owned the season.

While “The Lake” may not be Ray Bradbury’s most refined fiction, and still shows a young writer in his ascent, this is the story that started it all.

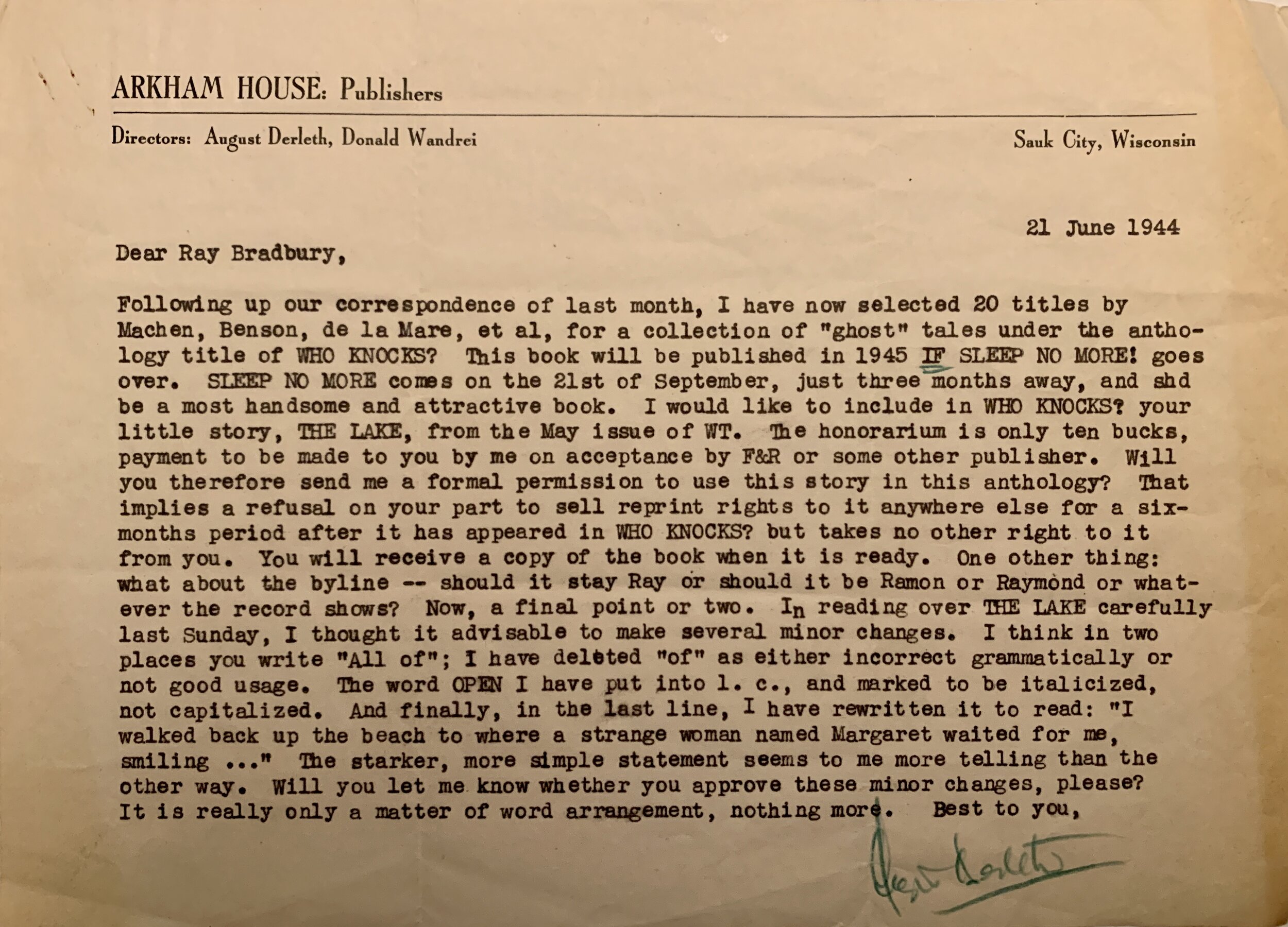

The Junem 1944 letter from editor and publisher August Derleth soliciting “The Lake” for inclusion in the anthology, Who Knocks? This would result in Ray Bradbury’s first publication in a book. (From the collection of Sam Weller.)

First Anthology Appearance: “The Lake” would mark Ray Bradbury’s first appearance in a book. In June, 1944, writer and Arkham House publisher August Derleth wrote to Bradbury, soliciting a short story for a forthcoming anthology of “weird” and supernatural short fiction he was editing for Rinehart & Co., entitled, Who Knocks? The story he wanted to include was “The Lake,” which had run that very month in Weird Tales. Two years later, in April 1946, Ray Bradbury would amble into Folwer Brothers Bookstore in downtown Los Angeles. It was there that he met a young bookseller named Marguerite McClure. Perhaps in an effort to impress her, he asked if they stocked Who Knocks?, informing her that he had a story in the book. Curious, Marguerite read the story that very day. “I was dazzled by the style of the story,” she told me in a 2001 interview. The macabre content wasn’t her literary cup of Earl Grey, as it were, but the writing was most impressive. This is how Ray Bradbury met Marguerite McClure. A little over a year later, on September 27, 1947, they would marry.

#3 “THERE WILL COME SOFT RAINS”

Where to Find It: The Martian Chronicles, The Stories of Ray Bradbury

EC Comics adaptation of “There Will Come Soft Rains” from Weird Fantasy #17. Art by the great Wally Wood.

First Published: May 6 1950, Collier’s

Plot Synopsis: On a post-apocalyptic Earth, an automated suburban home goes through its daily mechanizations even as all of its human inhabitants have been eradicated by nuclear devastation.

Backstory: Ray Bradbury talking about the story in Listen to the Echoes: The Ray Bradbury Interviews:

“I picked up the newspaper after Hiroshima was bombed and they had a photograph of the side of a house with the shadows of the people who lived there burned into the side from the intensity of the bomb. The Japanese people were gone, but their shadows remained. That affected me so much, I wrote the story.”

Critique: Ray Bradbury has called it “the human choice.” Technology can be used for the greater good, or it can lead to humanity’s downfall. Even with all the modern technological luxuries envisioned in “There Will Come Soft Rains,” from robot mice that vacuum, to a stove that cooks, Bradbury’s point is that humanity is the danger here, not technology. He was often deemed a luddite or a technophobe, but these labels are incorrect. He was not afraid of technology, he was afraid of it in the hands of the wrong people.

“There Will Come Soft Rains” was published less that 6-years after the dropping of the atomic bombs over Nagasaki and Hiroshima, and for this reason, it is impossible not to look at the story as Cold War literature. Bradbury was commenting on the proliferation of technology, the devastating nature of nuclear warfare, and the specter of death brought about by the advent of this new technology. It is telling that the story is in The Martian Chronicles, but does not take place on Mars, but, instead, back on earth. This is Bradbury’s most searing indictment of war and the existential threat of nuclear weapons. But even beyond the social commentary of the tale, it’s crowning achievement is in its execution. Taut and without a wasted word, this tragic and poetic tale unfolds without a single human protagonist. The main character is the house.

The title of this story reflects the growing influence of Bradbury’s new wife on his reading tastes. When they first began their courtship in April of 1946, Marguerite McClure introduced Bradbury to a trove of poetry, including the work of Pulitzer prize-winning, American poet, Sara Teasdale. In 1918, during world War I and the outbreak of the 1918 Flu Pandemic, Teasdale published the poem, “There Will Come Soft Rains” about nature’s ultimate indifference to humankind’s existence and eventual extinction. Bradbury’s story of the same name examines the very same themes. And If you look at the story titles in Bradbury’s first collection, Dark Carnival, and compare them to the story titles in The Martian Chronicles, the introduction of romantic verse by Marguerite McClure in Ray Bradbury’s life is immediate evident.

#2 “THE VELDT”

Where to Find It: The Illustrated Man, The Stories of Ray Bradbury

First Published: Under the title, “The World the Children Made,” September 23, 1950, Saturday Evening Post

Plot Synopsis: A husband and wife pamper their children by giving them a state-of-the-art nursery room, where dreams and fantasies come alive on the crystal walls. The room is a virtual-reality playroom-cum-television of tomorrow. When the children become dependent on the new technology, the parents endeavor to wean them from it. But the children aren't so willing to let go.

The original cover sheet for the final draft of “The Veldt,” dated December 27, 1949. (From the collection of Sam Weller.)

Backstory: Bradbury wrote the first draft of this story in two hours after typing the word "The Playroom" on the top of a blank page. He then envisioned what a children's nursery of the future might look like. It’s not a surprise that he had children on his mind. Bradbury’s first daughter, Susan, was born the same month he wrote the story. The Bradbury’s were living at 33 South Venice Boulevard at the time and he wrote this iconic story in this small, one bedroom apartment.